| Feature | Target |

|---|---|

| independent variable | dependent variable |

| predictor variable | response |

| explanatory variable | outcome |

| covariate | label |

| x | y |

| input | output |

| right-hand side | left-hand side |

2 Thinking About Models

Before we get into the details of models and how they work, let’s think more about what we mean when talking about them. As we’ll see, there are different ways we can express models and ultimately use them, so let’s start by understanding what a model is and what it can do for us.

2.1 What Is a Model?

At its core, a model is just an idea. It’s a way of thinking about the world, about how things work, how things change over time, how they are different from each other, and how they are similar. The underlying thread is that a model expresses relationships about various aspects of the world around us. One can also think of a model as a tool, one that allows us to take in information, derive some meaning from it, and act on it in some way. Just like other ideas and tools, models have consequences in the real world, and they can be used wisely or foolishly.

2.2 What Goes into a Model? What Comes Out?

In the context of a model, how we specify the nature of the relationship between various entities depends on the context. In the interest of generality, we’ll refer to the target as what we want to explain, and features as those aspects of the data we will use to explain it. Because people come at data from a variety of contexts, they often use different terminology to mean the same or similar things. The next table shows some of the common terms used to refer to features and targets. Note that they can be mixed and matched, for example, someone might refer to covariates and a response, or inputs and a label.

Some of these terms actually suggest a particular type of relationship (e.g., a causal relationship, an experimental setting), but here we’ll typically avoid those terms if we can, since those connotations may not apply to most situations. In the end though, you may find us using any of these words to describe the relationships of interest so that you are comfortable with the terminology, but typically we’ll stick with features and targets for the most part. In our opinion, these terms have the least hidden assumptions/implications and just imply ‘features of the data’ and the ‘target’ we’re trying to explain or predict1.

2.3 Expressing Relationships

As noted, a model is a way of expressing a relationship between a set of features and a target, and one way of thinking about this is in terms of inputs and outputs. A model takes in inputs and spits out an output that we hope is similar to the target. But how can we go from input to output?

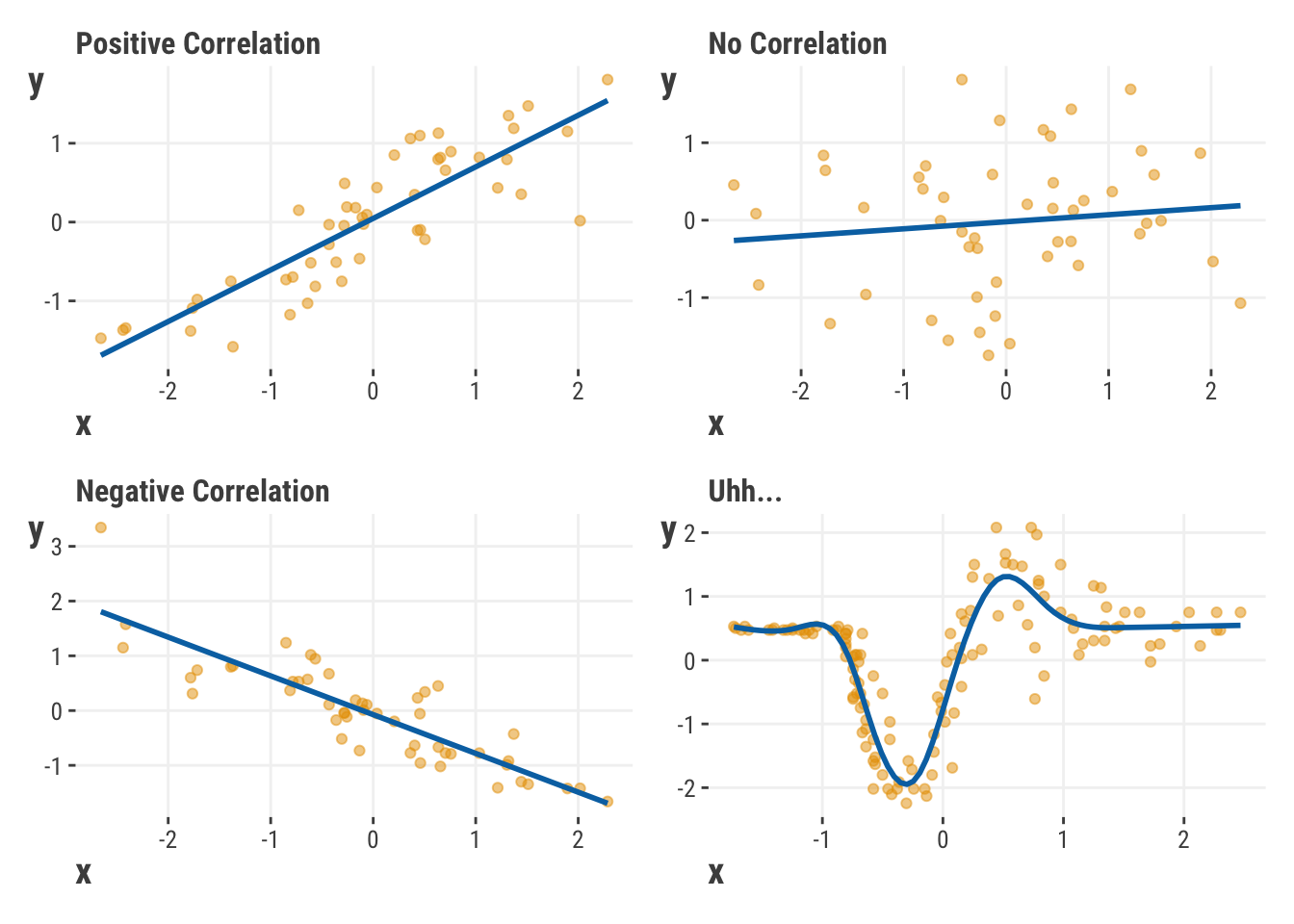

Well, first off, we assume that the features and target are correlated, that there is some relationship between the feature x and target y. The output of a model will correspond to the target if they are correlated, and more closely match it with stronger correlation. If so, then we can ultimately use the features to predict the target. In the simplest setting, a correlation implies a relationship where x and y typically move up and down together (positive correlation) or they move in opposite directions where x goes up and y goes down (negative correlation). But it can also get more complicated than that (Figure 2.1, bottom-right).

Even with multiple features, or nonlinear feature-target relationships, where things are more difficult to interpret, we can stick to this general notion of correlation, or simply association, to help us understand how the features account for the target’s variability, or why it behaves the way it does.

2.3.1 Mathematical expression of an idea

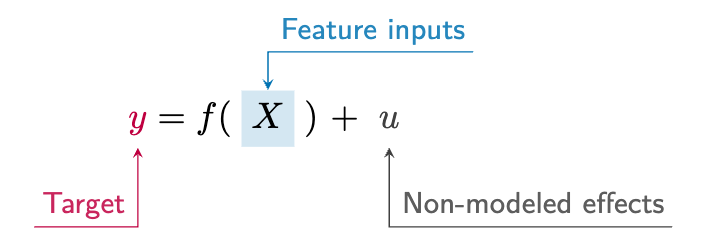

Models are expressed through a particular language, math, but don’t let that worry you if you’re not so inclined. As a model is still just an idea at its core, the idea is the most important thing to understand about it. The math is just a formal way of expressing the idea in a manner that can be communicated and understood by others in a standard way, and math can help make the idea precise. Here is a generic model formula expressed in math:

In words, this equation says we are trying to explain something \(y\), as a function \(f()\) of other things \(X\). The output of our model is \(f(X)\), but there is typically some aspect we can’t explain \(u\) that is also at play. This depiction is the basic form of a model used in data science, and it’s essentially the same for linear regression, logistic regression, and even random forests and neural networks.

But in simpler terms, we’re just trying to understand everyday things, like how the amount of sleep relates to cognitive functioning, how the weather affects the number of people who visit a park, how much money to spend on advertising to increase sales, how to detect fraud, and so on. Any of these could form the basis of a model, as they stem from scientifically testable ideas, and they all express relationships between things we are interested in, possibly even with an implication of causal relations.

2.3.2 Expressing models visually

Often it is useful to express models visually, as it can help us understand the relationships more easily. For example, we already showed how to express the relationship between a single feature and target in Figure 2.1. A more formal way is with a graphical model, and the following is a generic representation of a linear model.

This makes clear there is an output from the model that is created from the inputs (X). The ‘w’ values are weights, which can be different for each input, and the output is the combination of these weighted inputs. As we’ll see later, we’ll want to find a way to create the best correspondence between the outputs of the model and the target, which is the essence of model fitting.

2.3.3 Expressing models in code

Applying models to data can be simple. For example, if you wanted to create a linear model to understand the relationship between sleep and cognitive functioning, you might express it in code as follows.

lm(cognitive_functioning ~ sleep, data = df)from statsmodels.formula.api import ols

model = ols('cognitive_functioning ~ sleep', data = df).fit()The first part with the ~ is the model formula, which is how math comes into play to help us express relationships. Beyond that we just specify where, for example, the observed values for cognitive functioning and the amount of sleep are to be located. In this case, they are found in the same dataframe called df, which may have been imported from a spreadsheet somewhere. Very easy isn’t it? But that’s all it takes to express a straightforward idea. More conceptually, we’re saying that cognitive functioning is a linear function of sleep. You can probably already guess why R’s function is lm, and you’ll eventually also learn why statsmodels function is ols, but for now just know that both are doing the same thing.

2.3.4 Models as implementations

In practice, models are implemented in a variety of ways, and the previous code is just one way to express a model. For example, the linear model can be expressed in a variety of ways depending on the tool used, such as a simple linear regression, a penalized regression, or a mixed model. When we think of models as a specific implementation, we are thinking of something like glm or lmer in R, or LinearRegression or XGBoostClassifier in Python, or the architecture of a deep neural network. In our examples, we use functions where we will specify the formula that expresses the feature target relationships, or we will specify the input features and target in some fashion, e.g., as separate data objects called X and y. Afterward, or in conjunction with this specification, we will fit the model to the data, which is the process of finding the best way to map the feature inputs to the target.

2.4 Components of Modeling

It might help to also think about models, or the process of modeling, as having different aspects or parts. We can break our thinking about models into the following components.

Task

The task can be thought of as the goal of our model, which might be defined as regression, classification, ranking, or next word prediction. It is closely tied to the objective (loss) function, which is a measure of correspondence between the model output and the target we’re trying to understand. The objective function provides the model a goal - minimize target-output discrepancy or maximize similarity. As an example, if our target is numeric and our task is ‘regression’, we can use mean squared error as an objective function, which provides a measure of the prediction-target discrepancy.

Model

In data science, a model generally refers to a unique (mathematical) implementation we’re using to answer our questions. It specifies the architecture of the model, and as we will see, this might be a simple linear component, a series of trees, or a neural network. In addition, the model specifies the functional form, the \(f()\) in our equation, that translates inputs to outputs, and the parameters required to make that transformation. In code, the model is implemented with functions such as lm in R, or in Python, an XGBoostClassifier or PyTorch nn.Model class.

Algorithm

Various algorithms allow us to estimate the parameters of the model, typically in an iterative fashion, moving from one guess to a hopefully better one. We can think of general approaches, like maximum likelihood, Bayesian estimation, or stochastic gradient descent. Or we can focus on a specific implementation of these, such as penalized likelihood, Hamilton Monte Carlo, or backpropagation.

So when we think about models, we start with an idea, but in the end it needs to be expressed in a form that suggests an architecture. That architecture specifies how we take in data and make outputs in the form of predictions, or something that can be transformed to them. With that in place, we need an algorithm to search the parameter space of the model, and a way to evaluate how well the model is doing. While this is enough to produce results, it only gets us the bare minimum.

We will see demonstrations of all of these components throughout the book, and how they work together to produce results. Beyond these components, there are many more things we have to do to prepare the data for modeling, help us interpret those results, understand the model’s performance, and get a sense of its limitations.

2.5 Some Clarifications

You will sometimes see models referred to as a specific statistic, a particular aspect of the model, or an algorithm. This is often a source of confusion for those who are early on in their data science journey, because the terms don’t really refer to what the model represents. For example, a t-test is a statistical result, not a model in and of itself. Similarly, some refer to ‘logit model’ or ‘probit model’, but these are link functions used in fitting what is in fact the same model, which we’ll cover in detail later. A ‘classifier’ tells you the task of the model, but not what the model is. Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) is an estimation technique used for many types of models, not just another name for linear regression. Machine learning can potentially be used to fit any model and is not a specific collection of models.

All this is to say that it’s good to be clear about the model, and to try to keep it distinguished from specific aspects or implementations of it. Sometimes the nomenclature can’t help getting a little fuzzy, and that’s okay. Again though, at the core of a model is the idea that specifies the relationship between the features and target.

2.6 Key Steps in Modeling

When it comes to modeling, there are a few key steps that you should always keep in mind. These are not necessarily exhaustive, but we feel they’re a good way to think about how to approach modeling in data science.

Define the problem

Start by clearly defining the problem you want to solve. It is often easy to express in very general terms, but it is more challenging to precisely pin down the problem statement in a way that can actually help you solve it. What are you trying to predict? What data do you have to work with? What are the constraints on your data and model? What are the consequences of the results, whatever they may be? Why do you even care about any of this? These are all questions you should try to answer before diving into modeling.

Know your data well

During our time consulting in industry and academia, we’ve seen many cases where the available data is simply not suited to answer the question at hand2. This leads to wasted time, money, and other resources. You can’t possibly answer your question if the data doesn’t have the appropriate content to do so.

In addition, if your data is fraught with issues due to inadequate exploration, cleaning, or transformation, then you’re going to have a hard time getting valuable results. It is very common to be dealing with data that has issues that even those who collected it are unaware of, so always look out for ways to improve it.

Have multiple models at your disposal

Go into a modeling project with a couple models in mind that you think might be useful. This could even be as simple as increasing complexity within a single model approach – you don’t have to get too fancy! You should have a few models that you’re comfortable with and that you know how to use, and for which you know the strengths and weaknesses. Whenever possible, make time to explore more complex or less familiar approaches that you also think may be suitable to the problem. As we’ll demonstrate, model comparison can help you have more confidence in the results of the model that’s finally chosen. Just like in a lot of other situations, you don’t want to ‘put all your eggs in one basket’, and you’ll always have more to talk about and consider if you have multiple models to work with.

Communicate your results

If you don’t know the model and underlying data well enough to explain the results to others, you’re not going to be able to use them effectively in the first place. Conversely, you also may know the technical side very well, but if you’re unable to communicate the results in simpler terms that others can understand, you’re going to have a hard time convincing others of the value of your work. Communication is an essential component of the modeling process, and it’s something that you should be thinking about from the very beginning.

2.7 The Hard Part

Modeling is just one aspect of the data science process, and the hard part of that process is often not so much the model itself, but everything else that goes into it and what you do with it after. It can be difficult to come up with the original idea for a model, and even harder to get it to work in practice.

The Data

Model performance is largely going to come from the quality of the data and how you’ve prepared it, from ensuring its integrity to feature engineering. Some models will usually work better than others in certain situations, but there are no guarantees, and often the practical difference in performance is minimal. But you can potentially improve performance by understanding your data better, and by understanding the limitations of your model. Having more domain knowledge can help reduce noise and irrelevant information that you might have otherwise retained, and it can provide insights for feature engineering. Thorough data exploration can reveal bugs and issues to be fixed and will help you understand the relationships between your features and your target.

The Interpretation

Once you have a model, you need to understand what it’s telling you. This can be as simple as looking at the coefficients of a linear regression, or as complex as trying to understand the output of a hidden layer in a neural network. Once you get past a linear regression though, you need to expect model interpretation to get hard. But whatever model you use, you need to be able to explain what the model is doing, and how you’re ultimately coming to your conclusions. This can be difficult and often requires a lot of work. Even if you’ve used a model often, it may still be difficult to understand in a new data environment. Model interpretation can take a lot of effort, but it’s important to do what’s necessary to trust your model results, and help others trust them as well.

What You Do With It

Once you have the model and you (think you) understand it, you need to be able to use it effectively. If you’ve gone to this sort of trouble, you must have had a good reason for undertaking what can be a very difficult task. We use models to make business decisions, inform policy, understand the world around us, and make our lives better. However, using a model effectively means understanding its limitations, as well as the practical, ethical, scientific, and other consequences of the decisions you make based on it. It’s at this point that the true value of your model is realized.

In the end, models are a tool to help you solve a problem. They do not solve the problem for you, and they do not absolve you of the responsibility of understanding the problem and the consequences of your decisions.

2.8 Getting Ready for More

The goal of this book is to help you understand models in a practical way that makes clear the relationships we’re trying to understand with them, and also how models produce those results we’re so interested in. We’ll be using a variety of models to help you understand the relationships between features and targets, and how to use models to make predictions, and how to interpret the results. We’ll also show you how the models are estimated, how to evaluate them, and how to choose the right one for the job. We hope you’ll come away with a better understanding of how models work, and how to use them in your own projects. So let’s get started!

Just a side note, some refer to the observed target as the ‘true’ values. All data is measured with error, or simply just varies, so you won’t be dealing with ‘true’ values, but merely observed values.↩︎

This is a common problem where data is often collected for one purpose and then used for another, as with general purpose surveys or administrative data. Sometimes it can be that the available data is simply not enough to say anything without a lot of uncertainty, as in the case of demographic data regarding minority groups, for which there may be few instances of a particular sample. Deep learning approaches like zero/Few-shot learning isn’t applicable here, because there isn’t a model pretrained on millions or billions of similar examples to transfer knowledge from.↩︎